Hey folks, thanks for *check notes* … waiting two months for the supposedly weekly series of Questions to frame my week.

This week’s I will pose three Gojek-adjacent questions. Why specifically Gojek? Well, though you can pose similar questions in the context of other large successful companies/private endeavors in Indonesia, Gojek represents one of the most successful in recent memories. There’s this incredible (relative) concentration of talent, capital, and resources, with a culture driven by impact, that solves real problem for millions of people in Southeast Asia … such that it’s often kinda weird to see the founders of Gojek not solve the local civilizational inadequacy that exists around them (or at least, not make a public stab at them). À la J. Storrs Hall, you can explain this seeming inadequacy in at least two ways: a failure of imagination & a failure of nerve. Through this week’s questions, I want to make an at least marginal improvements at solving the ‘imagination’ part of the problem. So, without further ado, …

Q1 What explains the rituals forming behind gig-driver communities in Indonesia (and elsewhere)?

Humans are really good at pattern-matching (communities of them, even more so), and it’s been the story of our civilization that we create elaborate stories about how the world works that not only are ruthlessly optimized for fitness but also to satisfy our own curiosities, that doesn’t always correspond to reality. And it seems like a feature of our times that we have so much slack in our modern civilization that we are able to live with beliefs that don’t really correspond to reality, beliefs that are not straightly fitness enhancing.

There’s this general observation that we see when we have a group of humans interact iteratively with some opaque, complex systems and try to benefit from its interactions with them. At the limit, we expect ‘instrumental rationality’ and ‘epistemic rationality’ to converge with each other (due to Dutch Book arguments), but as we’re embedded, bounded agents, we face a very real trade-off between having good, well-specified, parsimonious, predictive models of reality vs having quick, easy-to-calculate, portable, reliably-winning, biased-for-survival models for action. Some ways this have been remarked upon:

- Kahneman’s System 1 & System 2 modes of thought.

- James Scott’s Metis vs Episteme, Illegibility vs Legibility, Anarchist Communes vs High Modern Authoritarians; also this really fun series of article by samizdat.

- “That’s the wrong question and it valorizes white institutions and white ways of knowing and being and structuring society in really problematic ways.” - legendary twet

- Pengetahuan-pada-umumnya vs Kearifan Lokal

One man’s modus ponens is another’s modus tollens; and the usual modern way of responding when seeing these ‘folk knowledge’, ‘kearifan lokal’ is to take the modus tollens like so:

- If we adopt this messy system of knowledge that’s evolved against its local niches for an extended period of time, then we will gain fitness in our local niches

- We in fact have seen that groups of humans who have adopted this system of knowledge have lost, reproductive-fitness-wise … we haven’t seen their peoples, or cultures, or ideas take hold in our modern society.

- So, through modus tollens (i.e. taking the contrapositive of 1), we shouldn’t adopt this system of knowledge.

The post-rat response to this is illustrated through Chesterton’s Fence: it’s unwise to destroy a fence you see erected in the middle of the forest when you don’t know what the reason behind it being erected, it might be the case that the fence was put there to keep dangerous animals out. In other words, it’s almost likely the case that when you have an evolved system built through patchworks and not through some totalizing first principles, it’s not going to have some legible, cleanly-separated set of goals that it pursues. Throughout its exposure to its environments, it’s gonna optimize for multiple problems at the same time (just like how biology is so complex). ‘Gain Fitness’ is in fact a multi-objective problem, and when you do away with some systems of knowledge that’s been adaptive for an extended period of time (but not adaptive when seen through e.g. its value in the World Economy), you might risk trading off against some valuable things that you won’t know about until it’s Too Late.

To conclude a bit, we know that true knowledge should converge with the fact that it’s useful, but as humans we face trade-offs between truth and usefulness (all models are wrong but some are useful), and we sometimes underestimate how useful some evolved systems of knowledge are, to our own detriment. This is essentially a problem of “How Do We Deal with Wrong but Useful Knowledge?”.

So, all that above is a long introduction to the question that I want to ask here. Gojek drivers face this management-by-algorithm that’s opaque, and acts as an intermediary, a market maker if you will, between the drivers and the passengers. And I claim that the above dynamics also exists in Gojek drivers’ interaction with the platform.

But first, a segue on why Gojek’s interaction with its drivers the way it is: one tendency that you see among ‘platform’ tech monopolies is that they try to commoditize their complement, where (from Gwern),

“companies seek to secure a choke point or quasi-monopoly in products composed of many necessary & sufficient layers by dominating one layer while fostering so much competition in another layer above or below its layer that no competing monopolist can emerge, prices are driven down to marginal costs elsewhere in the stack, total price drops & increases demand, and the majority of the consumer surplus of the final product can be diverted to the quasi-monopolist.”

Some illustrative examples (still from the ever-resourceful Gwern),

- Microsoft achieving market dominance in Operating System through standardizing the PC standard from an IBM-dominated to a ‘Wintel’-dominated one.

- Google sponsoring browser, making Chromium as an open source project, decoupling browser choice with search engine choice to maintain its monopoly on search.

Gojek also acts like this, in that it tries to commodify both its passengers, and drivers (also true of all ‘platform economies’). On passenger-side, though, demand is already quite commoditized: you can easily treat different orders from different passengers as practically fungible, that only differ in one important respect (origin and destination location).

This is arguably not true when you look at the situation driver-side. Gojek came in an environment where the dominant players are fragmented, local ojek pangkalan with its idiosyncrasies that are little monopolies of its own. This means that the existing stock of drivers can’t be treated as fungible & interchangeable. Drivers have different equipment, with their own unique local knowledge, and with different preferences that might be very sticky (e.g. certain drivers might only want to receive orders from/to particular locations). This is a problem because this makes (at least some subset of) drivers as price-setters, and not price-takers, which takes away a portion of the consumer surplus from Gojek.

On local knowledge of drivers

It used to be that one of the biggest barriers to entry to becoming a driver in a particular locale is your knowledge of routes and roads and landmarks, so much so that there were (are still) examinations that test aspiring drivers’ knowledge of their city. But due to Moore’s law making compute easily available in everyone’s pocket (smartphones), and Google’s monopoly on search making them able to provide free map tile & routing service for everyone (Google Maps), there is practically no more moat by having a back-of-the-hand knowledge of your city.

The pressure to commoditize drivers is also strengthened further by the fact that ride-hailing monopolies have increasing returns to the scale of the networks over which they have command. A big part of passengers’ decision to use Gojek stems from the fact that Gojek has many drivers (who often use Gojek exclusively), and the converse of this is also true. Thus, insofar that drivers idiosyncrasies induce very lumpy, unpredictable, and uneven supply; and insofar that this feeds back negatively into would-be passengers’ decision to use the platform; it’s in the best interest of the network to enforce some kind of standardization over its drivers.

To achieve the commoditization of its drivers, Gojek employs hard rules and soft incentives, such as

- An obligation to wear the characteristic bright green jacket and helmet

- Mandatory use of driver apps, even for functions other than receiving orders, like navigation, viewing earnings.

- Heavy penalty against taking orders off-app, this includes enforcing anonymized contact and funneling all driver-passenger comms in-app

- Heavy penalty against refusing orders (unspecified times) in a row for a period of time

- Ban against using other competing ride-hailing apps

- Platform-set fares, drivers can’t negotiate prices with customers; this makes service predictable for customers and positions drivers as price-takers

- Centralized payment system, that reduces direct financial interactions between drivers and passengers

- Bonus and incentive schemes to even out distribution of supply, like bonus that’s tied with the number of trips, or bonus on certain periods of times for drivers in certain cities

- Some gamified system of internal status

- Some algorithmic matchmaking procedure that ostensibly optimizes for some relevant performance measure (number of trips, rating of drivers/passengers, total rupiah amount, trip fulfillment, bid/order acceptance, etc)

Most of these rules and incentives are not obligatory, and their enforcement is not perfect, but the sum effect of them to the pool of Gojek drivers looks eerily similar to what it would’ve looked like if the drivers were to be organized in a command-and-control manner like you’d see in most other companies. This is essentially the thrust of the argument that ‘Drivers as Workers’ groups have: if it quacks like a duck then we should probably recognize it as a duck.

This means that the view that we have of ride-hailing platforms like Gojek that are shaped like “Gojek is just a place where willing sellers of the service of motorcycle rides and wiling buyers of said service meet and transact with each other” are at best incomplete and at worst a plausible-deniability veil for Gojek lobbyists.

On the partner (mitra) - worker (pekerja) distinction

But I still think that the partner (mitra) - worker (pekerja) distinction is meaningful here, or at least that they should exist in a spectrum here instead of a binary. The key thing that most Gojek drivers trade stability for is fundamentally choice. Gojek drivers at the end of the day are not forced to follow certain schedules, or take orders from certain places; and insofar that they are forced to do something then we should regulate them less like a partner and more like a worker. We’ve also got to remind ourselves that Indonesia pre-Omnibus Law for Job Creation (Cipta Kerja) had a very rigid labor law, one of the most generous in the world for the amount of severance & redundancy pay it mandates to be given to workers. The fact that Gojek has scaled so quickly is also an evidence towards there being a huge latent supply of willing drivers that couldn’t provide the service because there were no visible/contestable markets they could offer their service in.

This is also not to say that the commoditization itself is bad. In fact it’s a central theme of humanity’s progress over the past few centuries that we achieved them through the slow and gradual unraveling of barriers to trade amongst ourselves, enabling labor and capital and technology and information to flow to where they’re needed the most. I want to continue to remind people that at the very least the first order effect of Gojek is good: there are millions of contrafactual transactions totaling trillions of rupiahs in economic value that wouldn’t have happened if it were not for the existence of ride-hailing platforms like Gojek.

Again, we have so many things (at least in Indonesia’s big cities) that we now take for granted.

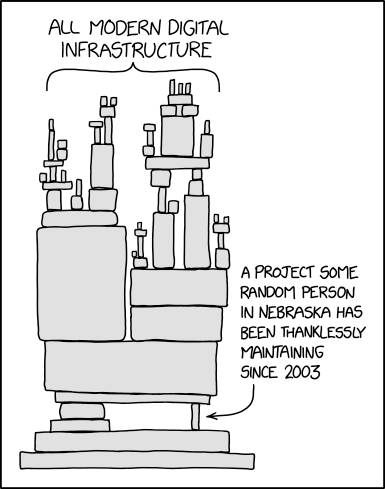

What makes Gojek (and other ride-hailing platforms, again to be clear) unique relative to other ‘platform’ monopolies here is that they employ opaque matchmaking algorithms heavily (unlike e.g. Tokopedia, or Amazon, which convey more information through reviews and prices). And unlike with explicit rules/incentives, it’s often unclear to the drivers why (interpretability moment) the algorithm nudges them to act out in a certain manner. And viewed in this light, it’s pretty clear that this story is very similar to the story of alienation that played out in the industrializing economies of the 19th century1.

There’s argument to be made that the transition should be made clearer to its drivers, and I can see how the argument for greater recognition for drivers as workers resonates emotionally here. Even if in the long run we’ll reach an equilibrium of Gojek drivers and passengers that maximizes surplus for both of them (and all of us), it’s not clear that the short-term adjustments won’t be painful for a large subset of the population. Insofar that this can be reduced, we should take steps in doing that.

With all that being said, whether you think this Great Commodification of Drivers2 is (net) Bad or Good, this phenomenon (of Gojek Drivers) results in a few interesting things, that I’m asking questions about:

- What are some of the specific driver heuristics that they use to maintain some notion of performance? There’s talks about ‘akun gacor’, particular accounts with favorable bidding power than others, and the folk, unfalsifiable theories on how to maintain it: is it about never rejecting orders? about being online at specific times? about physically being near a certain gofood merchant before they even get an order?

- The existence of a low-grade arms race between legibility and illegibility. The platform’s goal is to have a totally legible, commoditized, and standard supply of drivers. But this legibility imposes costs, reduces autonomy, and may drive down their revenue as they become more replaceable. For example, Gojek introduces measures to atomize and track drivers (in-app chat, anonymized numbers). drivers respond by creating illegible, off-platform counter-networks (whatsapp groups for sharing tips, coordinating, and warning each other). Gojek’s algorithm dictates routes and incentives; drivers respond with technological insurgency like GPS-spoofing apps (

tuyul) to game the system. - One way you can think of this legibility-illegibility dynamic is that the legible represents some low-dimensional mapping, the emphasizing of some useful aspects of reality, from the high-dimensional potentially unknowable noumenal reality. In other words, because all agents in our universe found themselves to be a subset of this universe (‘Embedded Agents’), they must necessarily compress the universe into a workable world-model3 to orient themselves and determine next course of action in. This means that a consequentialist-enough agent would want to make a (legible) map of reality that’s close to the (illegible) reality. One obvious way you can do this is to make your map as faithful to reality as possible. Another way you can do this is through making reality as close to your map as possible. This interaction is made even more dominant insofar that the particular ways of your map-making enable you to influence the reality even more (as it is the case with our ‘maps’ of science and technology4, or statecraft and ideology5). All this is to say, one way the ‘legible’ ‘black-box’6 algorithms of Gojek affect reality is through making its drivers more malleable to the implied ‘shape’ of the driver that the revealed preferences of millions of customers want. What is this shape of the Ur-Driver? A common theme of market failures is coordination problem (where locally optimal decisions yield in globally inadequate, sometimes horrifying, equilibria), and how different methods of aggregating preferences seems to yield inconsistent results (e.g. elections in a per-individual basis vs per-community/corporate basis, or democratic elections vs democratic market). Is this the shape of Ur-Driver that we want to exist in our society?7

More: on how we should deal with network-effect monopolies.

No more questions, I think that’s enough for now lol. If you’ve come this far, whew, thanks for bearing with me! Hoped it made sense hahah.

Footnotes

-

Theories about Alienation are essentially theories about encountering an alien, deterritorializing force that knows no bounds, no taboos, and profanes everything it touches.

(à la Nick Land - Capitalism as an alien entity reaching out across time seeding itself to humanity’s past to assemble itself in the future) (which is crazy because how intelligent something must be to anticipate the various ways humanity could evolve in the future) (the more boring explanation is that Capitalism is just like pipes, it’s an instrumentally useful way of allocating resources to their most productive uses, just like pipes are a useful form factor to move liquid)

You can understand phenomena like Luddism, which I struggled to understand before, why would anyone be against increasing productivity (╭ರ_•́). But this is easier to understand when you see this a first-contact story, of a group of people meeting an alien force that is the constant flattening into money (‘exchange value’ as Marx would term it) of everything by the market.

I have some sympathy towards this view of society, but we often have very romanticized view of the past, and deep bias for the status quo, such that it’s often hard to really grok how improved the life of the median person has been since our economy grew exponentially (i.e. how it seems normal to just expect total economic output to grow a fixed X amount of percent), and how we can still be better. ↩

-

Marxists think this is very similar to the concept of reserve army of labor, whereby capitalists deliberately keep a surplus of workers in deteriorating conditions to keep labor costs low - which tbf again has that conflict vs mistake theory texture to it.

It might have some grain of truth to it? In that one of the key factors that enabled Japan to succeed in its textile industrialization was through keeping wages depressed whilst productivity went up, i.e. doing away with the prevailing piece-rate mechanism to compensate labor and instead replacing it with hourly wages. ↩

-

And this has been a very productive area of scientific speculation, some stuff I’m reminded of when talking about this map-territory dynamic: Parable of Predict-O-Matic, The Whispering Earring, On Exactitude in Science, Garden as control over nature. ↩

-

Marx’s 11th Thesis on Feuerbach, “The philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is, to change it” ↩

-

One way to resolve this tension is to clarify, legible as opposed to what? And in this case, those legible maps that enable more capabilities to flow into them (or more specifically, those maps that interact well with the prevailing institutions that we use to allocate resource and status) are the maps that would win out in this dynamic. And this aggregated preferences need not be at all legible to its constituent parts (!). ↩

-

Again, it is the case that for thousands of years we have chosen stability over the dynamic creative destructive power of the market. And it turned out that, we were at least directionally wrong on the cost/benefits calculation of applying the awesome powers of the market in our society. ↩